Stablecoins in Africa (Part II)

The case for local stablecoins

USD stablecoins don’t solve Africa's USD shortage problem at scale, nor do they reduce Africa's ~$400B USD leakage we identified in Part I.

While crypto enables a sophisticated digital economy, its success in Africa could become its failure if it just makes dollarization more efficient.

Intra-African trade reached $208 billion in 2024, outpacing trade with the rest of the world. However, approximately 95% of African trade is cleared outside the continent through global banking institutions. This depletes already scarce USD reserves, while adding friction and costs.

In Part I, we discussed how stablecoins solved Africa's USD liquidity fragmentation problem between the banking and parallel markets.

In Part II, we examine why USD stablecoins alone aren't enough, how local stablecoins can transform intra-African trade and credit markets, and the best implementation approaches.

We argue that local currency stablecoins represent the next evolution of financial innovations in Africa - while USD stablecoins create significantly better plumbing for global value exchange, local currency stablecoins promise better plumbing for local economies. These two forces go hand in hand in driving a digital economy revolution.

The Cost of Dollarization

Some ask, "Why can't we use USD stablecoins for everything?"

Locally issued currencies remain entrenched in society and commerce worldwide. They facilitate buying/selling local goods and services, paying taxes, receiving government services, accessing debt, and conducting daily transactions. Importantly, governments use their own currencies to stimulate economies - something no government will willingly surrender.

Very few countries have dollarized their economies and use USD as their primary currency; Zimbabwe is one example following periods of hyperinflation.

When a country fully dollarizes, what does it surrender?

Monetary sovereignty: the ability to print currency to finance government spending or stimulate the economy

Monetary policy: the ability to set interest rates, have the central bank serve as lender of last resort, and adjust currency value to influence trade competitiveness

Debt issuance: the ability to issue domestic and international debt in their own currency, creating harder budget constraints

This represents economic and financial amputation, surrendering core instruments ALL countries use to prosper, including USD's issuer.

Even if we don’t go as far as full dollarization, using USD in all aspects of cross-border trade adds extraneous pressure that traps African countries in a vicious cycle of currency devaluation.

Routing regional trade through USD and global institutions carries high transaction costs (8-20% fee for SME cross border payments, or 4-5% for large scale transactions).

When central banks maintain large foreign reserves to cover import needs, paradoxically, it can contribute to further depreciation of the local currency - demand for foreign currency to accumulate reserves often puts downward pressure on the local currency. There are opportunity costs for the USD sitting in reserve versus deploying it in the productive economy.

USD stablecoins offer better pipes for the same broken system - they don't fix the inflow/outflow imbalance or prevent dollarization risk. If Africa's most sophisticated financial solutions only use USD rails, dollarization will grow exponentially.

The Genius Act accelerates USD stablecoins integration into traditional financial markets - a positive move for stablecoin adoption. The same liberalization of USD stablecoin issuance also centralizes USD flows through US financial institutions, putting African users back under blanket blacklisting or sanctions risks for entire populations - either as a result of geopolitics, low trust in African financial institutions, or real AML risks. We risk repeating the exact same patterns of the old gated financial system. The promise of internet native money that transcends borders and institutional biases could be squashed fast.

USD stablecoins will keep being powerful in plumbing African economies with the rest of the world, and that is a net positive. But dollarizing Africa cripples those economies, which is bad for the people who live there, and bad for Africa's trading partners who have much to benefit when Africa’s economy is 10x.

In a stablecoin-dominated digital finance world, the best chance for African currencies to survive and maintain relevance is to bring them onchain.

Stablecoin advantage over CBDCs

Digitizing African currencies on blockchains is not a novel concept. In fact, Nigeria ran the world's second-largest CBDC experiment: the eNaira.

Launched in 2021, the eNaira's implementation has been widely regarded as a failure, predominantly based on lack of large-scale adoption. By 2022, only 1.15M Nigerians had ever used the eNaira (0.5% of the population), with an average of 14,000 transactions weekly. Reports indicated that 98.5% of eNaira wallets remained inactive within a year of launch.

The eNaira failed because it did not interoperate with existing financial tools people use. It was built on a private database that didn’t communicate with other databases. It offered nothing special compared to banks: no differentiated deposit interest, no additional forex access, or different limits than banks have. Instead, the eNaira offered a more complicated and worse user experience. Bad and inconsistent rural internet in Nigeria made the eNaira less appealing.

A government-controlled platform for cash circulation didn't attract user trust. "People don’t trust the government to hand over their financial transaction information directly to them." For the world's second-largest crypto adopter, the eNaira was worse than fiat because of high government control and oversight risks. The market preferred trading Naira fiat with crypto instead of eNaira.

The eNaira experiment showed that central banks aren't best positioned to drive financial innovation and lead public distribution. CBDCs also face security risks because of how centralized they are. Downtimes, hacks, breaches, or contract failures are all existential risks for monolithic, centrally-managed local currency implementations.

The Local Stablecoin Opportunity

What new market coordinations are possible with stablecoins that were otherwise difficult to achieve? We focus on two key areas: powering intra-Africa trade with stablecoins while unifying formal and informal markets, and unlocking new forms of credit through better currency devaluation risk management.

Where can stablecoins create more efficiencies within existing capital flows? We focus on improved payment rails within African economies, and better streamlined fiat to USD orchestration.

1. Intra-African Trade

The most compelling case for local stablecoins lies in transforming intra-African trade, where existing USD dependency creates unnecessary friction and cost.

Intra-Africa trade already dominates the USD stablecoin flow through major African stablecoin services: HoneyCoin sees 40% of its $100M-$150M monthly volume, while other orchestrators report up to 90% of flows settling between African countries.

The $208 billion of intra-Africa trade is about 15% of all trade activity, but it’s growing at 8% a year versus 5.8% with the rest of the world. African countries spend about ~$5B USD a year on intermediary fees to trade with one another. FX infrastructure powered by local stablecoins can shift a significant amount of these trades to local currencies instead of relying solely on USD.

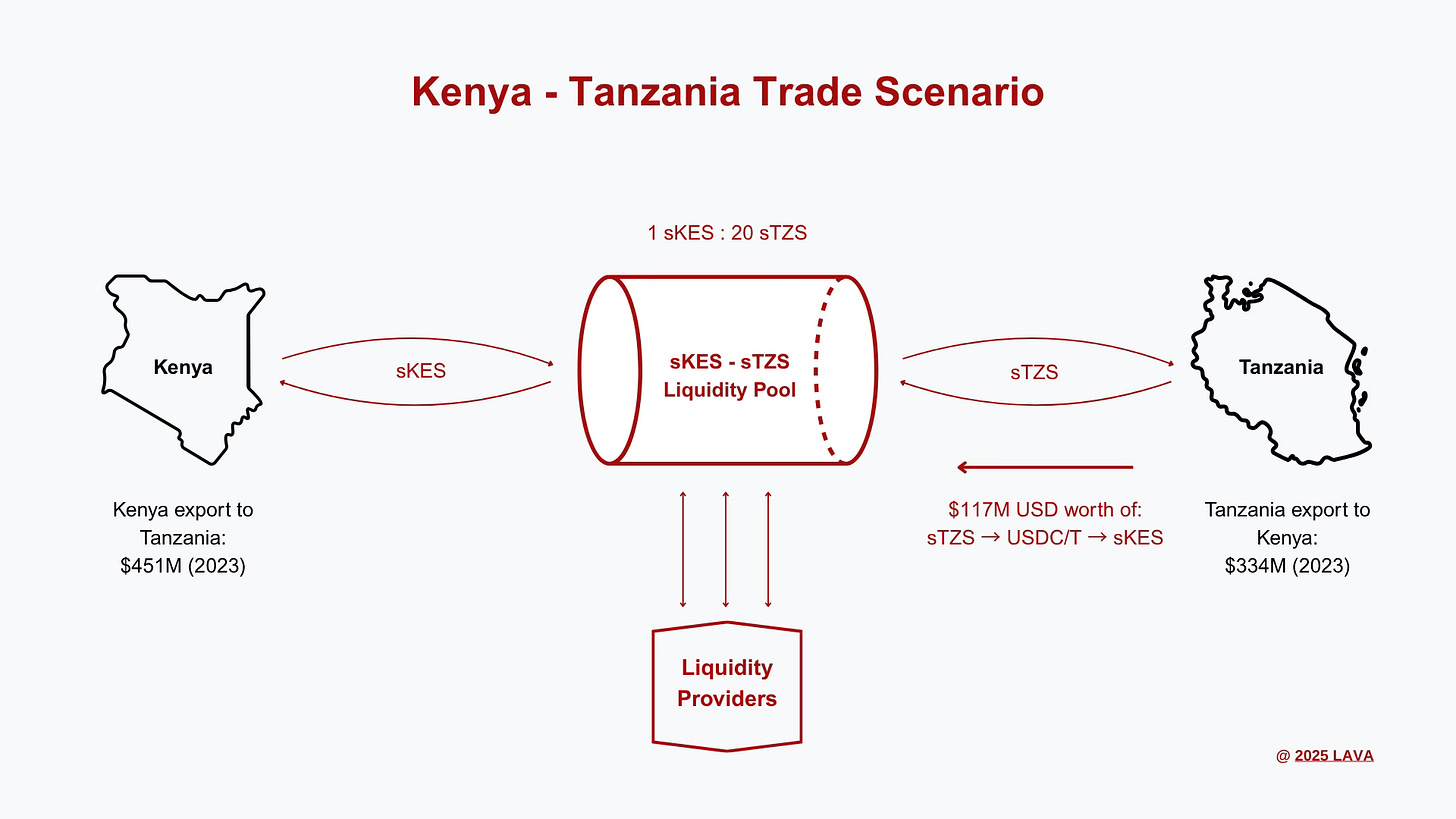

Below is a simplified example of two way trade between Tanzania and Kenya.

Kenya export to Tanzania (2023): $451M

Tanzania export to Kenya (2023): $334M

Currently, both countries’ central banks must buy and maintain USD reserves to fulfill these trades. USD-to-local currency conversion occurs across multiple financial institutions and informal Forex networks.

To illustrate one of the many ways stablecoins can be used here, let’s look at transactions in sKES for Kenyan Shillings and sTZS for Tanzanian Shillings - both example tokens for this illustration. One approach is to create a liquidity pool, with ratios set by respective value against the USD exchange. At current rounded estimates, 1 sKES = 20 sTZS, where 1 USD is roughly 130 KES and 2,600 TZS. This ratio is balanced based on exchange rates at a given time.

With ample liquidity in the pair and distributed volume throughout the year, the vast majority of the trade flow between the two currencies can happen without touching USD. To balance the difference, Tanzania would need to acquire a minimum of 15.2B sKES (worth $117M USD) through USD stablecoins, while the remaining $334M in bilateral trade could settle directly through the sKES-sTZS pool. Similar to DeFi Automatic Market Makers (AMMs), liquidity pools can maintain pre-determined ratios while arbitrageurs ensure market-aligned pricing.

USD continues as a powerful unit of account (how each local currency is valued), but less relevant as a medium of exchange for the majority of this trade corridor.

How these systems get implemented determine the type of liquidity attracted, incentive mechanisms to all participants, and role for arbitrageurs (if any). Ultimately, mechanisms that empower price discovery and full market participation from the largest banks to small shop holders stand a high chance of success.

The mechanism for Kenya-Tanzania trade can be scaled across other African corridors.

While research and experimentation is already happening with onchain FX, we need more in order to scale these infrastructures to serve the majority of trading corridors.

There is enough incentive to explore this direction further, especially considering the existing high fees everyone pays for cross-border transactions, USD scarcity within banks, and the growing number of market-driven liquidity providers already participating in fiat-USD stablecoin pools.

Closed or open systems?

When designing systems for trade flows, a natural inclination for governments is to build internal systems, which promise the type of legibility and control that states are used to.

One example is PAPSS (Pan-African Payment & Settlement System), a centralized platform on a private ledger that facilitates payments between African banks. Its stated goal is to tackle USD dependence for intra-Africa trade.

PAPSS works through multilateral net settlement: instead of settling every transaction individually, it aggregates all payments between participating central banks every 24 hours, with final settlement in USD/EUR only for net positions. Coordinating multiple institutions at scale is a remarkable achievement on its own. Other efforts are attempting to reach similar goals.

Better coordination amongst central banks is a net positive for the continent, as a lot of liquidity flows through them. However, initiatives like PAPSS have structural challenges that get in the way of achieving their intended goal. Local stablecoins on open and permissionless rails address these challenges:

Stablecoins can unify the banking and parallel market liquidity where all types of players can participate in open markets. When African currencies already have multiple rates, closed systems breed price fixing and manipulation, which inevitably drives liquidity out (see Part I). Markets prefer true price discovery. Two separate systems are more likely to fail, with liquidity gravitating toward the path of least resistance: USD.

Open systems are more resilient because they can be credibly neutral. Open systems are governed by rules and protocols, so competing parties can participate without fear of rules being rigged, transactions being censored, or exclusion. Everyone from central banks to small scale market actors can participate, which is precisely what reduces the cost of coordination amongst multiple sovereign nations.

Open systems utilize the full capacity of programmable money to facilitate atomic swaps that have no counterparty risk, to automate flows based on pre-defined rules and conditions, customizable fee structures (e.g. specific slippage rates for exotic corridors), and build regulatory compliance into smart contracts. Parties can manage multiple interests, incentives, and risks (e.g. 5%+/- range between sKES-sTZS pools).

Open and private databases can be composable with each other while maintaining privacy and sovereignty. Using Zero Knowledge Proofs, participants validate information from a private database (e.g. balance, transaction history) and only communicate that proof without requiring counterparty trust. High compliance and verification standards can be achieved without compromising privacy for individuals, institutions, or governments.

Africa’s best chance to address dollarization risk is to create systems for all public and private actors to participate openly.

How can we drive progress at a speed no single entity could ever match? That is the promise of blockchains, and that is the speed of execution of Africa's growth.

2. Unlocking credit markets

Currency risks impact credit access

Africa has a significant credit gap across all sectors, and currency risks directly affect how much credit is available and its cost. The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates a $402.2B annual financing gap to increase Africa’s productivity. In addition, an annual $68B - $108B infrastructure financing shortfall and a $140B SME credit gap limit Africa’s growth.

SMEs seeking credit turn to fintech startups, table banking networks, and micro-lending enterprises for credit. Those in Nigeria and Kenya pay between 3%-30% monthly interest for uncollateralized loans. Lenders who raise capital in foreign currency convert it to local currencies and pass on inflation risk to borrowers, leading to higher interest rates and higher chances of default.

Inflation and devaluation drives even the best performing infrastructure investments into Africa to negative returns, where financing happens in USD but revenues are in volatile currencies.

As a result, demand for borrowing in local currency grows higher when there is currency devaluation. Some within the AfDB suggest large scale projects that generate revenue in local currency, instead of borrowing in USD / EUR, to pool natural resources and “facilitate borrowing in African accounting units”. In crypto terms, this is equivalent to the tokenization of local assets.

De-risking African credit with stablecoins

Local stablecoins have a pivotal role in unlocking credit markets by offering better ways to manage devaluation risk, especially when capital originates in another currency, and by creating more ways to utilize Africa’s untapped assets.

Let’s break this down with an example:

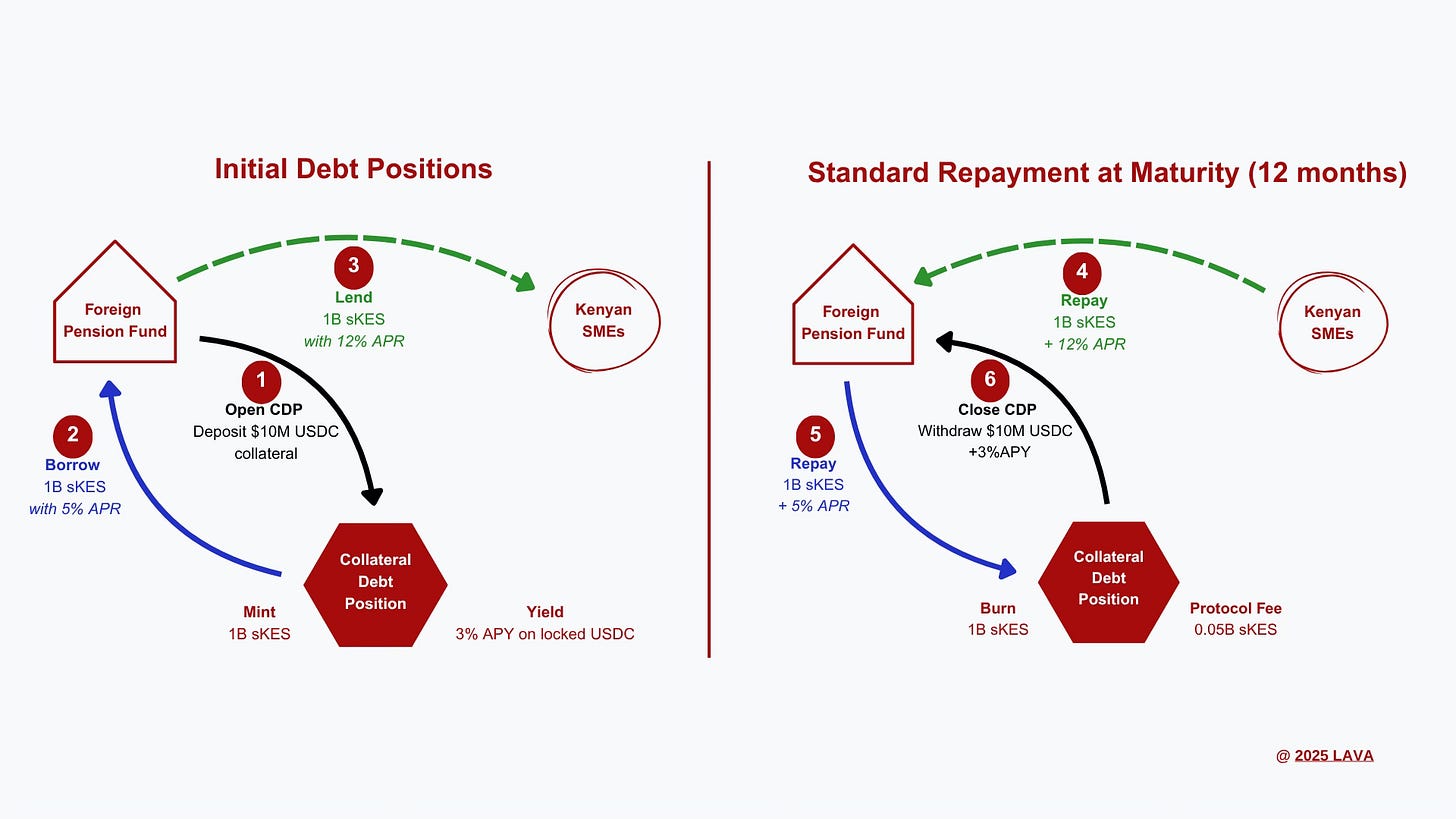

A foreign pension fund uses Collateralized Debt Positions (CDPs) to lock $10M USDC as collateral and mint 1B sKES at 5% annual interest paid to the protocol. They need to pay back 1.07B sKES in 12 months to redeem the $10M USDC.

The fund lends the sKES to Kenyan SMEs and earns 12% annual interest, while also earning 3% yield on their locked USDC collateral.

At maturity, the fund’s exposure to FX risk is limited to the 7% interest differential rather than the full $10M principal.

In this example, we replace the need to convert USD to local currency at the point of lending, mitigating currency devaluation risk.

Opening new credit marketplaces

Different mechanism designs allow all parties to play along the risk curve in more ways than previously available. Stablecoins facilitate more avenues to pool, distribute, recoup value and manage risk. We can pool debt positions across tens of thousands of borrowers and trade them in secondary markets - potential liquidity incentivizes more lender participation. Collateralized USD stablecoins can yield low risk interest while serving as collateral.

Africa has $4 Trillion of untapped assets (e.g. pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, forex reserves, gold etc.) often deployed into short-term and low risk assets. Could Africa’s pension funds deploy into longer term financing deals if there is a liquid secondary market? Can locked USD serve as leverage to mobilize untapped local capital, and have secondary markets to attract even more liquidity? These are interesting problems to solve.

Participation in Africa's growth will be more efficient with local currencies than foreign currencies, as that's where deeper local liquidity can be accessed. Tokenized securities (e.g. stocks and bonds, minerals) can be pooled, used as collateral, leveraged, fractionalized, tracked and easily transferred to facilitate new forms of financing. The “African accounting units” that the AfDB colleagues shared suddenly shift into an executable concept.

Stablecoins don’t single handedly change credit markets. They allow for open marketplaces where the smallest of the small players and the largest players can all participate, where new business models are possible.

USD stablecoins have proven the speed and scale for financial coordination that is possible. We can now use local stablecoins to reshape how money moves and how financial services are delivered across Africa.

3. Affordable and Accessible Payments

Mobile money in Africa represents the closest concept to stablecoins - the digital equivalent of cash on private databases. Easy movement between cash and mobile money have created the conditions for mobile money transactions to reach $1.1 trillion.

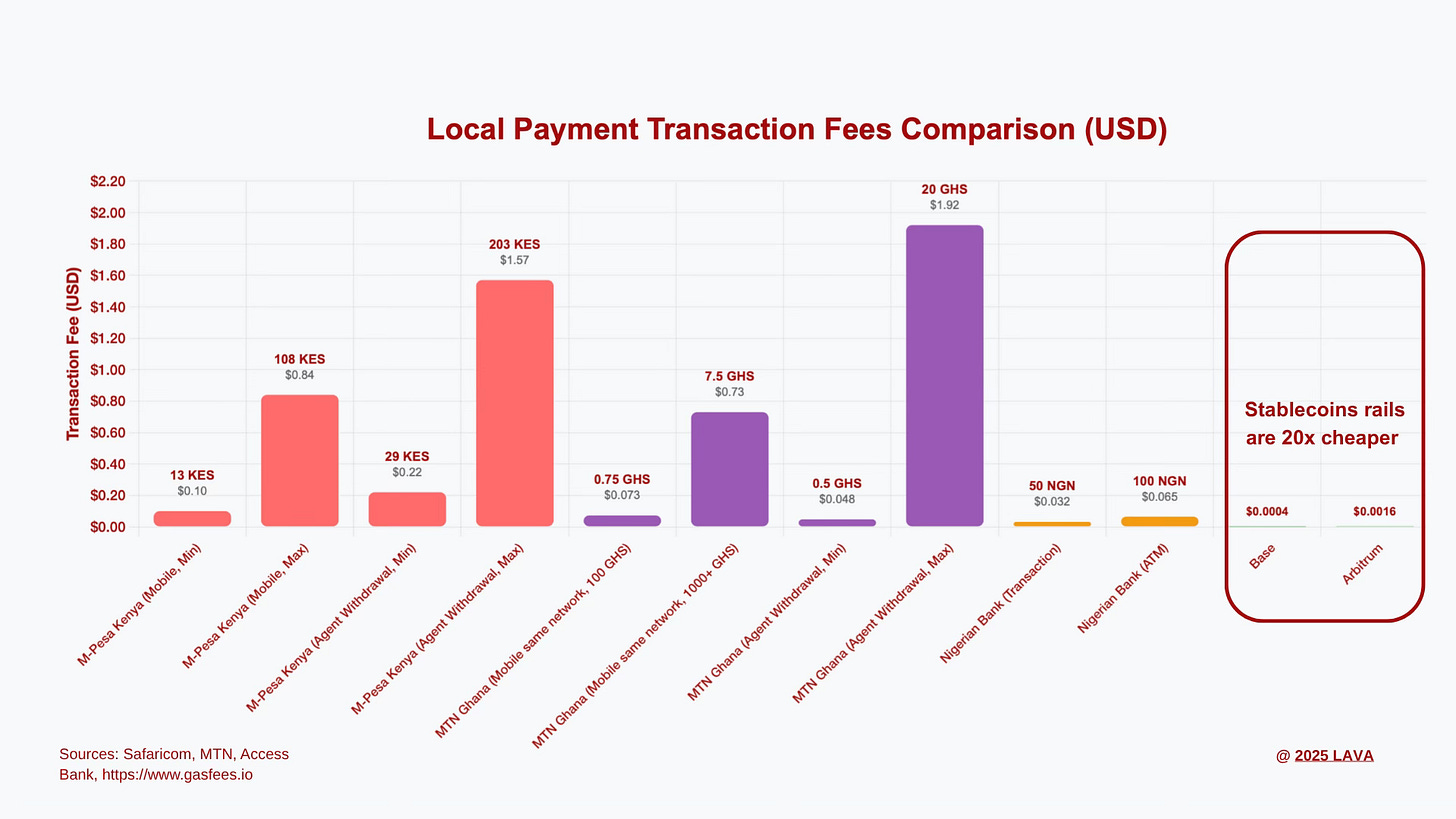

But mobile money and online banking aren't cheap. The chart below shows a cost comparison between three payment networks and stablecoin payments on leading L2s.

Beyond high price points, payment networks experience network issues during high loads. The two mobile money providers in Ethiopia (TeleBirr and MPesa) aren’t interoperable because they’re competing, so a user needs to transfer funds from one to a bank and then to the other.

Why will stablecoins offer better means of payment than private databases?

Cheaper for users, where payments on major L2s currently cost under $0.0016 - 20x cheaper than the lowest fee quoted above - regardless of the transaction amount, and can be even lower if stablecoin L3s launch for specific transaction types.

Instant settlements with less need to manage float across different payment providers, infrastructures, and geographies. If platforms use different stablecoins for the same currency, merchants can use AMMs to withdraw in their preferred stablecoin, protecting users from large monopolies incentivized to keep users on single applications.

Programmable money to facilitate smarter escrow services and creates clear, deterministic payment conditions. For example, escrowed prepayments indicate demand for milk in Kenya, and payments to smallholder dairy farmers happen at point of delivery.

Increased transaction capacity on public blockchains can reduce the type of network congestion issues that Web2/payment companies currently face.

There are a number of challenges to solve in scaling stablecoin payments. Distribution will be critical, because monopolies have less incentive to interoperate. Payment reversals are major components of existing payment networks, and currently not seamless with stablecoins.

4. Orchestration Efficiencies

Local stablecoins reduce friction in crypto-to-fiat exchanges. Current platforms that process billions of on/off ramps (e.g. Binance P2P, MiniPay, HoneyCoin, YellowCard, and more) would benefit from smoother swaps, moving high-friction manual processes to AMMs.

Local stablecoins can further reduce counterparty risk on P2P platforms. By using protocols like Paycrest to automate fiat-stablecoin transfers, liquidity providers can better hedge exchange rate fluctuations through auto orders instead of manual processes.

Trusted parties (an exchange or the stablecoin issuer) are still needed to redeem local stablecoins to fiat and vice versa 1:1. Aggregating trust and reducing friction for P2P on/off ramps can have multiple downstream effects for isolating risk.

How to Stablecoin?

The path to local stablecoins involves strategic trade-offs between speed of implementation and meaningful scale.

1. Reserve-Backed Stablecoins

The most scalable way to meet regulators' and market needs seen so far is reserve-backed stablecoins. There are tried and tested templates with USDC and USDT. cNGN, a consortium of financial and technology players, was created in Nigeria as the only licensed stablecoin issuer, soon after the eNaira failure.

Government bonds, treasuries, and money market funds (MMFs) act as reserves for stablecoins, where each unit of stablecoin is backed with 1:1 circulating money or a liquid asset. The regulator maintains monetary policy controls without significant added burden on central banks to drive mass market adoption. This strategy plays to regulators' and central banks' core strengths, and leverages private sector players to drive distribution.

The reserves are yield-bearing, creating high participation incentives. Multiple stablecoins will likely be issued per local currency instead of a single player. Even big players like MTN and M-Pesa could switch their current digital cash equivalents into stablecoins without significant disruption to user experience.

Our bet is that stablecoins which most seamlessly interoperate with different public and private databases will scale most and provide composability benefits.

There are also strategic upsides beyond stablecoin utilities. Tokenized bonds and treasuries can be made accessible in online marketplaces, potentially attracting more Foreign Direct Investment and USD into government coffers to buy African government debt. Currently, foreign institutions go through brokers to buy African bonds, which adds friction and cost (e.g. Harvard endowment). More evidence is needed to prove sufficient global demand for capital flow in and out.

Reserve-backed stablecoins offer existing financial institutions and new startups many roles across the value chain, so we expect fewer deterrents in this direction.

Launching reserve-backed stablecoins requires a conducive regulatory framework, especially to ensure the reserve asset exists at all times and risks are managed.

2. Crypto backed stablecoins

Crypto asset-backed local stablecoins are 'easier' to launch by deploying contracts but harder to scale to the size of a country’s economy. There are tested templates such as DAI and RAI.

The idea is simple: use some token (or basket of tokens) as reserve collateral and mint a stablecoin pegged to local currency as debt against that token. This requires liquidation mechanisms and collateralization ratios. Companies like Mento have been driving experimentation and scaling such mechanisms across multiple currencies.

The big value proposition is a permissionless way to issue local stablecoins, which can then be distributed to existing crypto users and beyond. The ideas of onchain FX can be tested with faster feedback loops, and scaled with resilient foundations.

The systemic risk for crypto backed stablecoins is that it is inflationary of local currency, introducing 'new' money into the system, and regulators don't have monetary policy control. It would be negligible in smaller amounts (even at $100Ms of volumes) but more problematic with higher issuance rates. Another risk lies in maintaining the peg, managing liquidation risks depending on reserve tokens used, and prevention of smart contract attacks to maintain user trust.

However, crypto backed stablecoin issuers can later swap (or complement) crypto reserves with tokenized bonds and treasuries, or other assets that meet regulatory needs in order to scale.

The Path Forward

Africa’s current financial systems interoperate over walls. Decentralized systems facilitate greater cooperation and participation, giving money powerful network effects.

If local stablecoins carry a fraction of their promise, our monies become equipped with such network effects that unlock new layers of economic activities.

What conditions are needed to test the hypotheses and reap the potential benefits of local stablecoins? Below are potential starting points.

Holistic Regulation, Not Just Compliance

The world hails MPesa as one of the greatest innovations in digital payments to come out of Africa. But when it started in 2007, MPesa operated in a legal gray area. There wasn't a comprehensive regulatory framework specifically for mobile money ready and waiting for M-Pesa's launch. Instead, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) adopted a ‘test and learn’ approach, where they allowed M-Pesa to operate and grow, observing its development and assessing the risks. Formal regulation for mobile money payment systems came in 2011.

A similar regulatory approach is needed for what stands to be a highly consequential digital economy innovation. We need to look at local stablecoins beyond mere compliance, and through the lenses of economic development, financial sovereignty, dollarization risk, digitizing financial services, and market structure.

It’s critical for governments to look at the risk and rewards from first principles, including lost upside and price of inaction. Local stablecoins also bring up fundamental questions about the roles African governments see themselves playing in a digital economy. Will they drive innovation at the forefront and take responsibility for executing on digitization of their economies? Will they set the rules of the game for the market to drive, and collect tax to reinvest it back in their economies? Or other combinations? A proactive approach is needed.

Sandboxes that enable experimentations of all types are going to be critical to offer insights on what and how to regulate.

Network Effects Strategy

Liquidity and distribution will continue to be key driving forces for any success in local stablecoins. A cold start creates the chicken and egg problem - how to bootstrap liquidity before demand?

Onchain FX could be a starting point to reach critical mass distribution, especially with the significant volume of USD stablecoin flows going into intra-Africa payments.

Powering traditional payment distributions could also offer different starting points. Be it powering the PAPSS network to facilitate intra-Africa trade, or enabling MTN, MPesa, or Orange to let users send and receive money across borders without leaving their native apps.

Large farming cooperatives could use stablecoins' programmability to indicate demand by escrowing funds into contracts, and release payments when orders are delivered, so producers have predictability and buyers have security.

Major lenders could use local stablecoins to offer credit and use their additional earnings from lower devaluation risk as well as additional yield on their reserve asset to significantly undercut the credit market.

Wherever stablecoin use meets actual demands, embedding network effects into the strategy allows greater liquidity coordination and gives participants first mover advantage.

Future Experiments

While local stablecoins’ long-term benefits are clear, it’s not certain where short-term traction is going to come from. For that reason, different types of experiments are needed.

As a startup or government, experimenting on multiple fronts carries greater risk too, and can confuse noise for signal. Within each experiment, keeping most variables consistent without boiling the ocean, and pushing boundaries on critical aspects can offer a path to scale.

We are seeing startups at different stages already pioneering local stablecoin innovations across Africa and many emerging markets (including cNGN, Mento, ZARP, Virtual Finance, NedaPay). We are looking forward to seeing more startups driving stablecoin experiments, from the short-term use cases to actualizing local stablecoins’ long-term promise.

Special thanks to cryptowanderer and See Eun for feedback and review.

Interesting… I reckon you’ve addressed a key issue which is a capital markets problem rather than a pure fx problem.

Now that stablecoins have solved the digitization of market access and liquidity on the fx spot via many more participants now than ever, we need tokenized risk transfer instruments to improve liquidity on the trade financing and risk management side… which is no doubt coming.

Why? Because it already exists informally - tokenizing it will simply reveal and make more efficient like it did for the fx and cash.

Problem with this glossy future: regulatory adoption + incumbents protection…

This has given me new pathways to think around the problems stablecoins will solve and create as they evolve.